techXXX

Mercedes M156 vs Maserati F136Y (4.7) vs BMW S65, Iconic Designs Compared

Today, I compare the Mercedes-AMG M156 6.2L V8, the Maserati F136Y 4.7L V8, and the BMW S65B40 4.0L V8 across seven aspects. These engines use equivalent technologies but differ appreciably in their design goals.

Today, I compare the Mercedes-AMG M156 6.2L V8, the Maserati F136Y 4.7L V8, and the BMW S65B40 4.0L V8 across seven aspects. These engines use equivalent technologies but differ appreciably in their design goals. I will come back to this in the conclusion.

Engine block

All three engines use a two-piece crankcase design with a bedplate that sandwiches the crankshaft with the upper block. The F136Y uses pressed-in steel liners. Maserati also uses studs for fastening the engine heads and the bedplate. Indeed, this engine block is directly from Ferrari and is the most premium setup.

The S65 uses an ALUSIL block. ALUSIL is known not to tolerate poor maintenance or high mileage. Part of the reason is that the microscopic silicon particles can be worn away: these silicon particles are themselves quite resistant to wear, but the aluminium to which they are bonded expand and contract during heat cycling. It also does not help that the pitch for oil film is much weaker in an ALUSIL block compared to honed steel. Supposedly, Molybdenum and ZDDP can help, but modern engine oils use these compounds sparingly.

The M156 uses plasma-sprayed NANOSLIDE coating on the cylinder walls. This is more resistant to wear than ALUSIL. One thing to note is that early M156 engines sometimes suffered head bolt failures due to a poor head bolt choice.

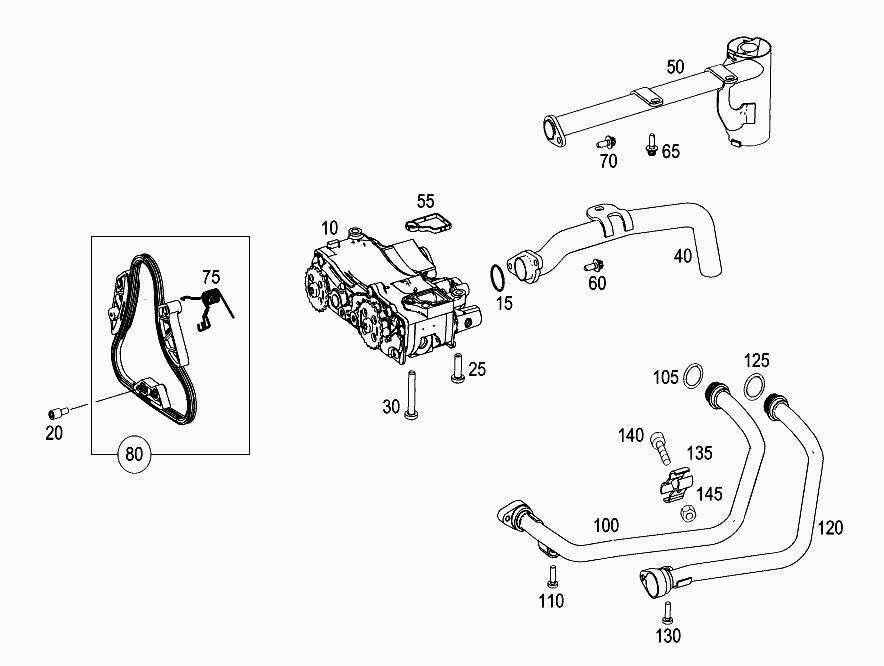

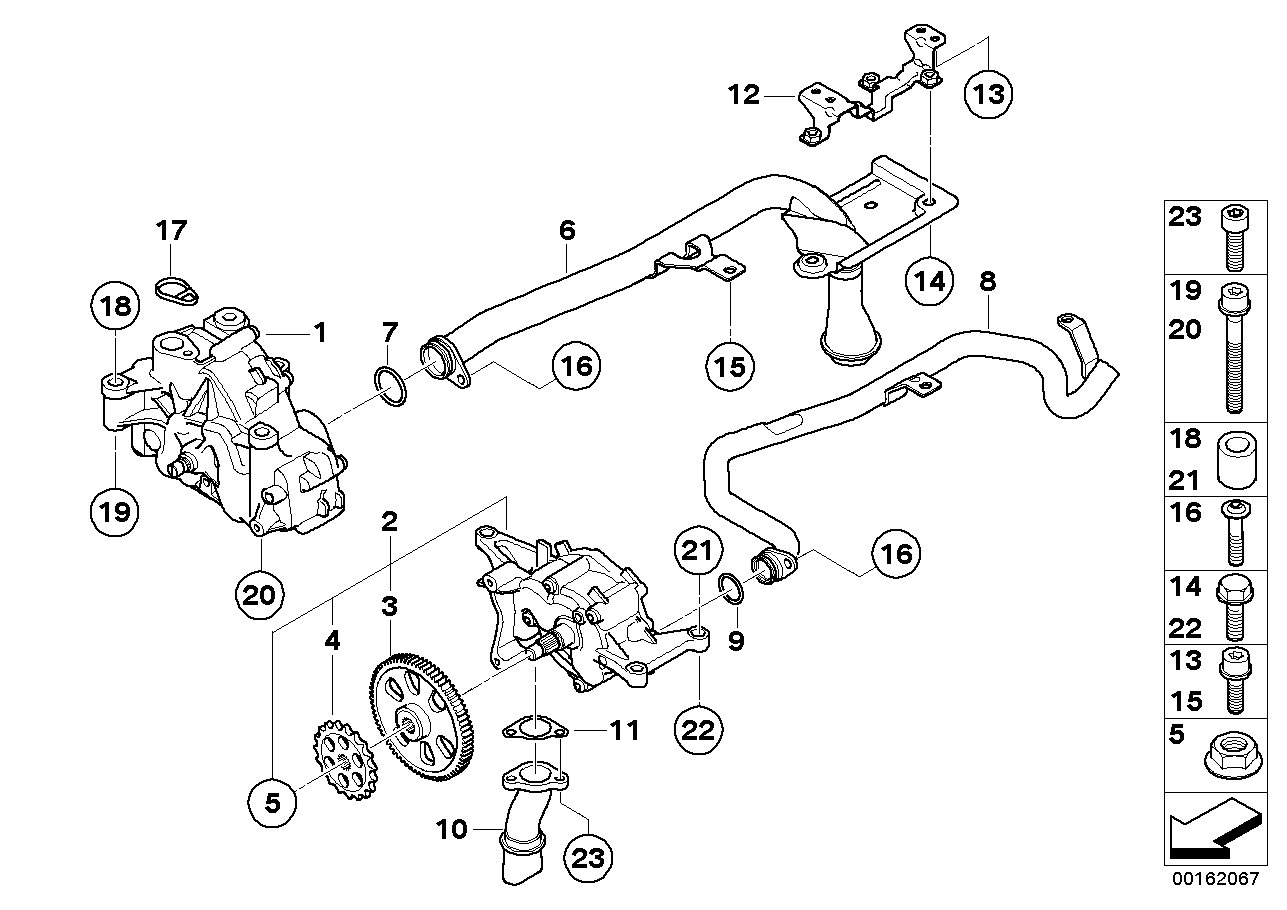

Oil pump

Both the M156 and S65 have a two-stage oil pump setup, one main pump and one scavenge pump. They are supposedly all internal gear type pumps (though I have not seen pictures of them opened). The M156 integrates the two stages in one housing but uses two external sprockets to drive them off the crankshaft with a chain.

The S65 uses the crankshaft to drive the scavenge pump directly. The scavenge pump then drives the main oil pump with a chain. It should be noted that the S85 V10 uses a similar setup but in place of the scavenge pump there is the VANOS pump.

Unfortunately, the F136Y uses a much simpler, somewhat awkward oil pump setup. This is because the F136 was designed to have a dry sump. It is left with a very long drive shaft. This is not the only place where Ferrari made sure that Maserati does not compete with its own cars.

Stroke ratio

The S65 has the highest stroke ratio, with 92mm bore and 75.2mm stroke. This gives it an 8400rpm redline and is the main reason many love this engine. However, BMW started to have widespread bearing problems right around when the S65 was introduced. This V8 suffers not only the typical BMW rod bearing problem but is also prone to spin main bearings. Many blame the tight tolerances that BMW uses, which surely does not help. There must be more to this story, but since BMW engineers cannot seem to figure it out, I am not going to pretend to know why.

The M156, on the other hand, is not as oversquare. While its 102mm bore is impressive for a European engine, AMG designed the M156 to have good driveability at low rpms. The M156 remains one of the torquiest NA engines ever with 630Nm. This was achieved, as old-timers would expect, with a large displacement. Still, the M156 was able to redline at 7250rpm in its base form.

The F136Y has 94mm bore, 84.5mm stroke, and 7600rpm redline. It is right in the middle of the two German extremes.

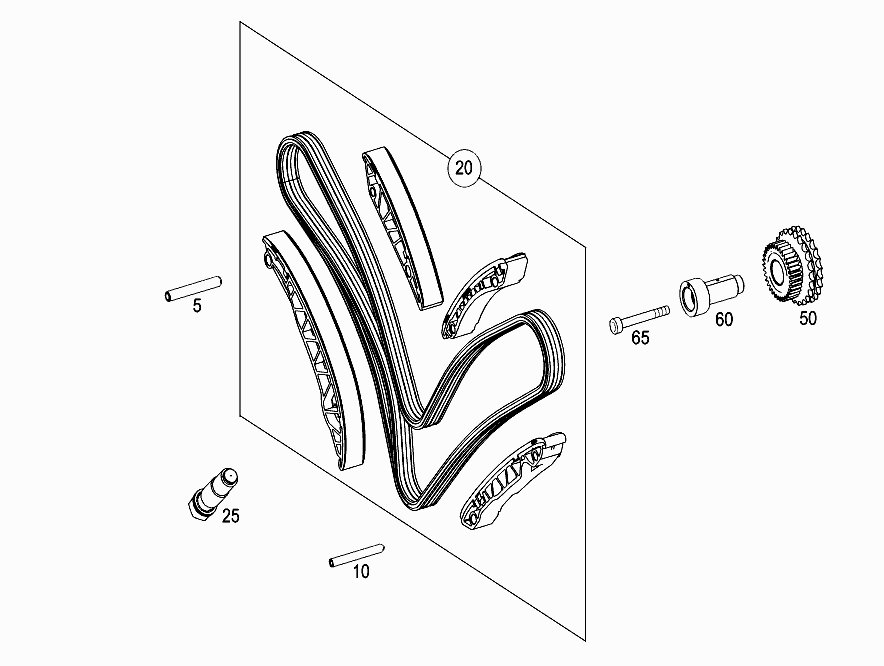

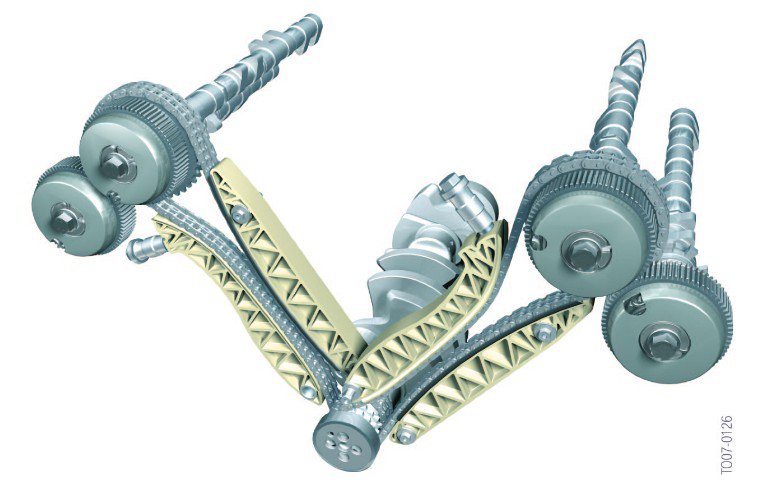

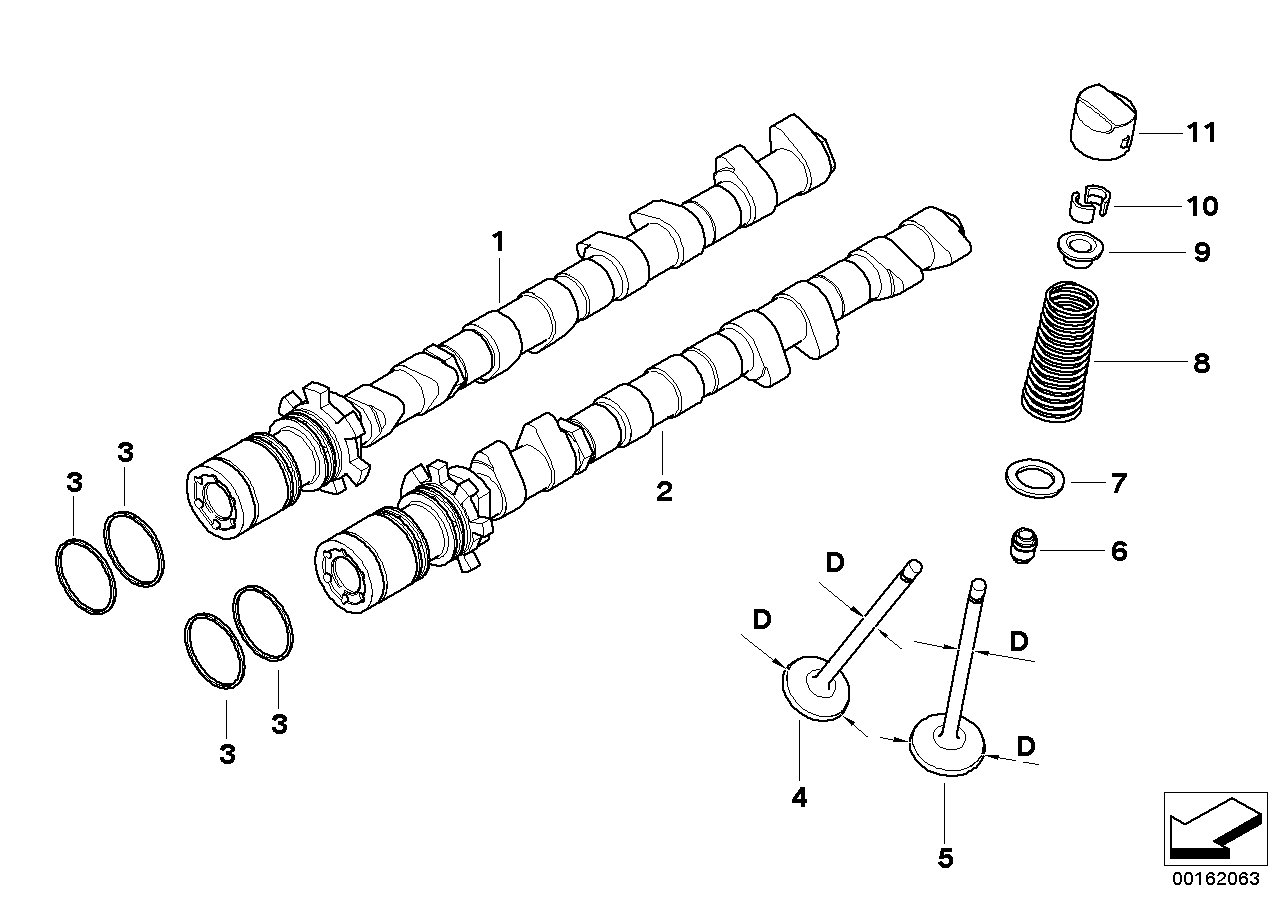

Timing setup

The M156 has the simplest timing chain setup for a DOHC V-engine. It uses a single duplex roller chain, one idler gear, and two intermediary gears. The latter drives the camshaft variators, or in Mercedes terms, camshaft adjustors.

The S65 also uses duplex roller chains, but there are two of them. Each chain drives only the intake camshaft variator, which drives the exhaust side with straight cut gears. This setup is optimal for high engine speed reliability. It is truly exceptional for BMW, which usually has very weak timing chains.

The F136Y uses a complex timing chain setup with three simplex roller chains. This is typical of modern Ferrari engines and seems to be quite reliable.

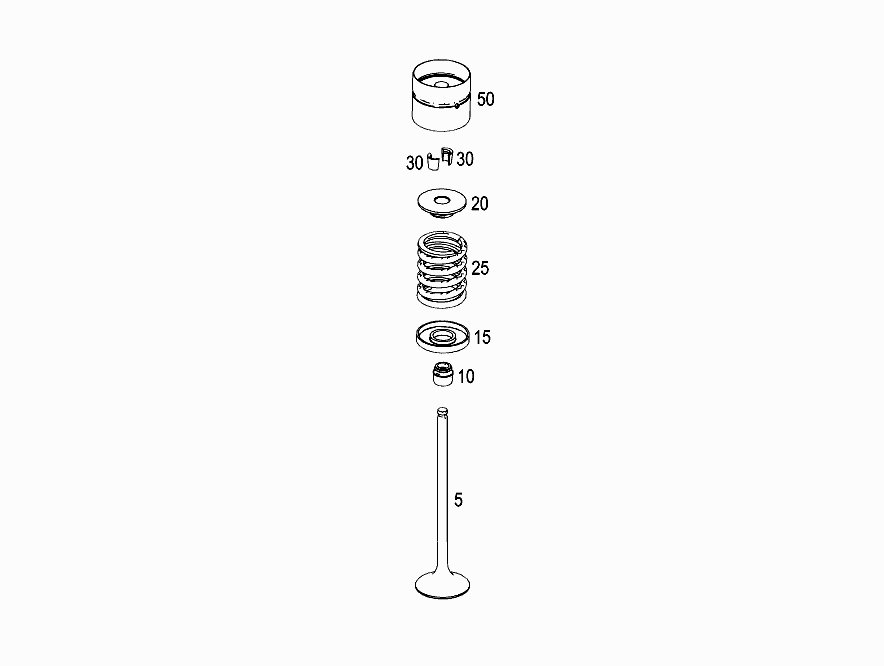

Lifters

All three engines use flat tappet hydraulic lifters, which should not be found in such expensive engines as roller lifters are more durable for high-performance applications.

The M156 and F136Y both use the flat-base-type. This is the simplest hydraulic lifter design. With the Mercedes, unfortunately, it is also a main failure point. Theories as to why has been raised, as this design is usually reliable, finding its way to many legendary Toyota engines. The most convincing to me is this: The M156 uses high valve lift and correspondingly a high-tension valve spring. This adds to the pressure between the camshaft lobes and the lifters. As the engine is also high-revving, the flat surface of this type of lifters is inconducive to oil film strength. Supposedly, an oil high in ZDDP (Zinc dialkyldithiophosphates) should be used. However, modern oils have little ZDDP, because it damages the catalytic converter. Using stronger, upgraded camshafts may not be wise, as the harder cam lobes may wear out the lifters sooner.

The S65 uses a radius or crowned hydraulic lifter. While still not as good as the roller type, the crown of this lifter helps distribute forces more evenly and appreciably increases longevity. The problem with the S65 is that its valve springs can break.

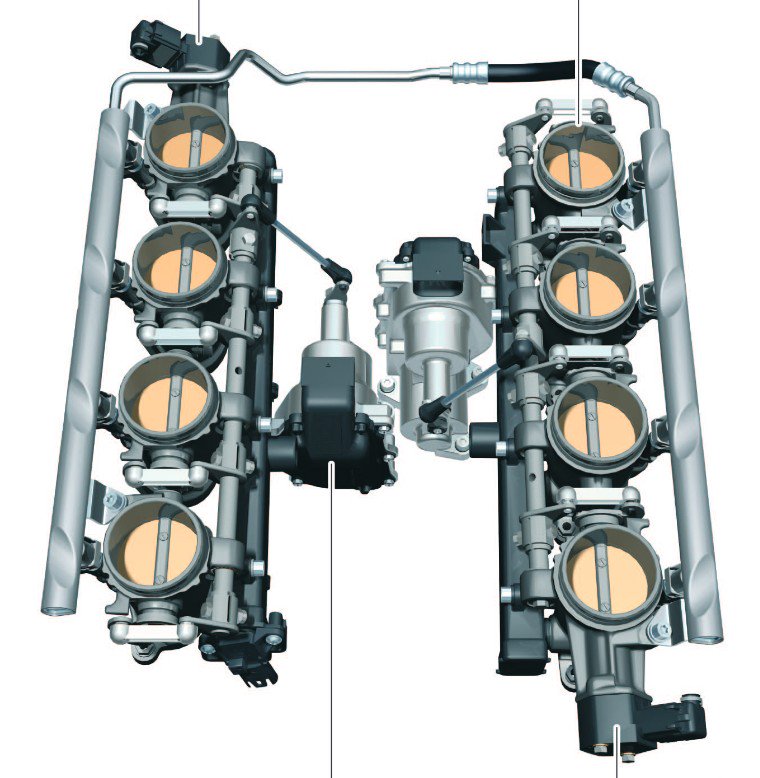

Intake

The S65 uses individual throttle bodies, a feature that all naturally aspirated M engines shared. This gives the S65 presumably the best throttle response. Of course, the two throttle body actuators are a failure point, also a common theme across BMW M engines.

The M156 uses two throttle bodies inside the intake manifold assembly. The magnesium intake manifold corrodes overtime.

The F136Y uses just a single throttle body. This is again how Ferrari made sure that the Maserati did not compete with its own vehicles.

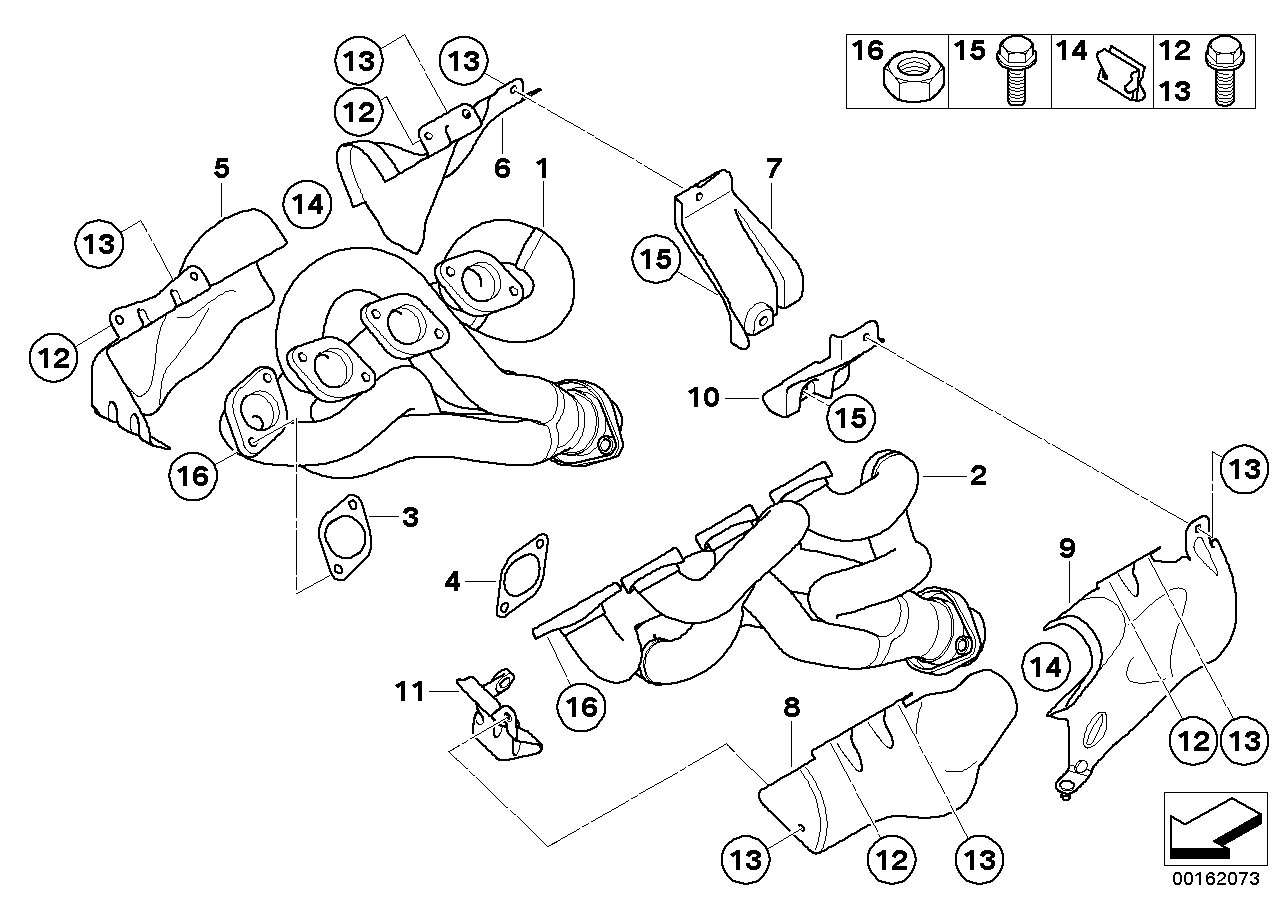

Exhaust

Both the S65 and F136Y use equal-length exhaust headers. This setup reduces back pressure. It also seems to produce a more pleasing exhaust note.

The M156 uses a standard, el cheapo exhaust manifold. Nevertheless, the engine is known for its exhaust note.

In conclusion, the S65B40 is the closest to a racing engine among the three. However, it is unusually unreliable even for a BMW. I think only those who intend to track their cars should look into it.

The M156 was designed as a platform for racing, and its robust short block shows. However, Mercedes builds on this foundation for racing, and the stock engine is more suitable for street use. In my opinion, using an oil high in ZDDP is crucial.

The F136Y has the best engine block. However, Ferrari made conscious choices to bring the engine down a notch. In my opinion, it is a good alternative to the M156 in street use.