techXXX

Ranking All Six V10 Engines Ever in Production for Road Cars

Today, I rank all six (or eight) V10 engines ever in production for use in road cars.

Today, I rank all six (or eight) V10 engines ever in production for use in road cars. Before I begin, however, I want to highlight two characteristics of V10 engines: bank angle and engine balance.

First a bit of history: Inline-5 and V10 engines had been difficult to build in petrol guise, because it is virtually impossible to fuel them correctly and efficiently with a single or an even number of carburetors. V10 has been more common in diesel guise for trucks, boats, and generators, because diesel engines have always been fuel injected. V10 petrol engine became possible with the broad application of fuel injection.

When it comes to bank angle, we see two general types: 72-degree and 90-degree. Because a four-stroke engine fires every 720 degrees of crank rotation, a 72-degree bank angle is the most natural for even firing order. It has a small first and second order rocking couple. However, the following engines with 72-degree-ish bank angle are not equipped with a balance shaft.

V10s with 90-degree bank angle are usually based on V8 engines with two additional cylinders. When the crank journals are not split, counterweights on the crankshaft can balance out the engine, but an odd firing order is usually used with 54-degree and 90-degree intervals. It is also possible to use an 18-degree split crank pin to achieve even firing order; this is better balanced than the 72-degree V10 but not perfectly so. Still, we can see that Volkswagen used balance shaft.

Lastly, I want to mention that with very few exceptions, a V10 is always more enjoyable and fuller of character than a V8, beating out even many V12s.

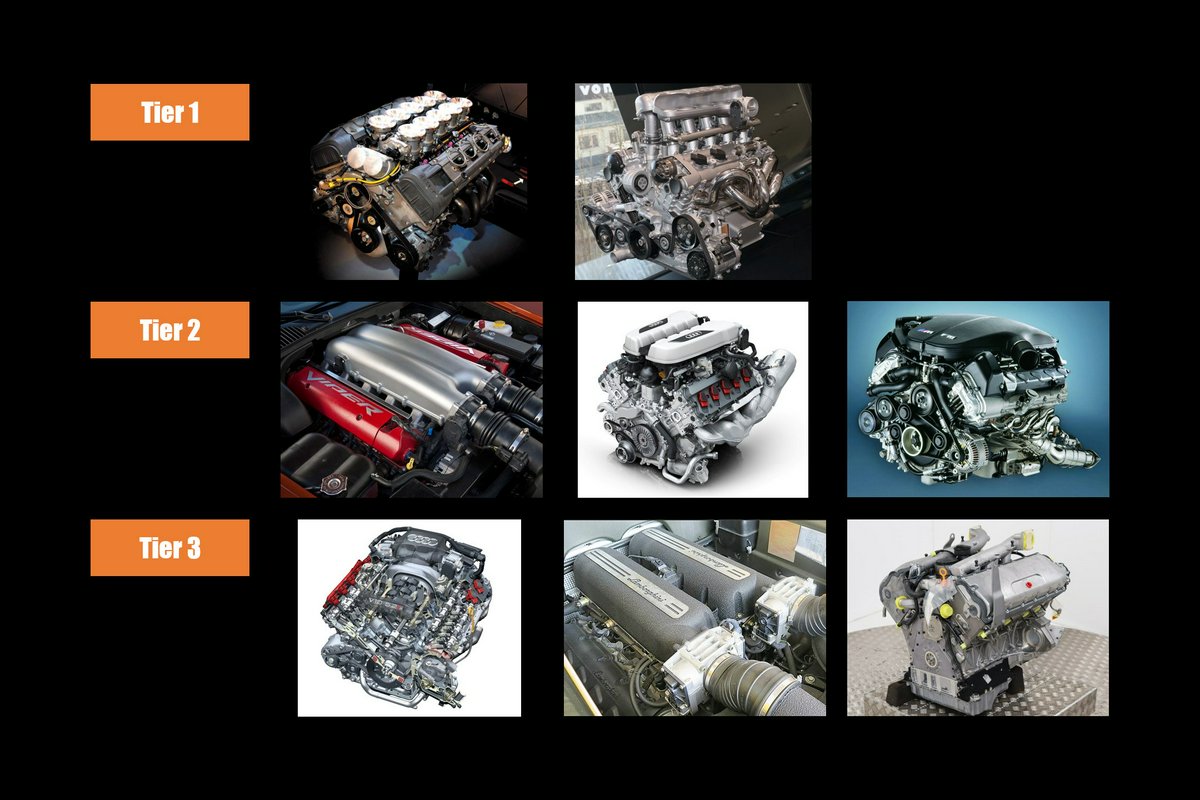

Tier 1

Toyota 1LR-GUE

The first in Tier 1 in my book is Toyota’s 1LR-GUE found in the Lexus LFA supercar. Co-developed with Yamaha, this engine is the only one on this list designed from the ground up for its destined application. It is also the only unit with a true 72-degree bank angle. Still, despite its over-square design, the 1LR is more compact than most V8s.

Toyota achieved this with the use of many exotic materials, including magnesium alloy for the cylinder head covers as well as titanium alloy conrods, valves, and rocker arms. Unsurprisingly, individual throttle bodies and dry sump lubrication are used.

The 1LR-GUE has a lightweight rotating assembly and no balance shaft, making it the closest one can get to an F1 racing engine in a road car. Most notably, the engine has a redline of 9000rpm, but the ECU only cuts the fuel supply at 9500rpm. It broke the world record for revving from idle to redline in 0.6 second. Also noteworthy is the used of an unconventional firing order that gives it a characterful sound track.

All these qualities make it the Number 1 for me. It also helps that the LFA is a gorgeous car.

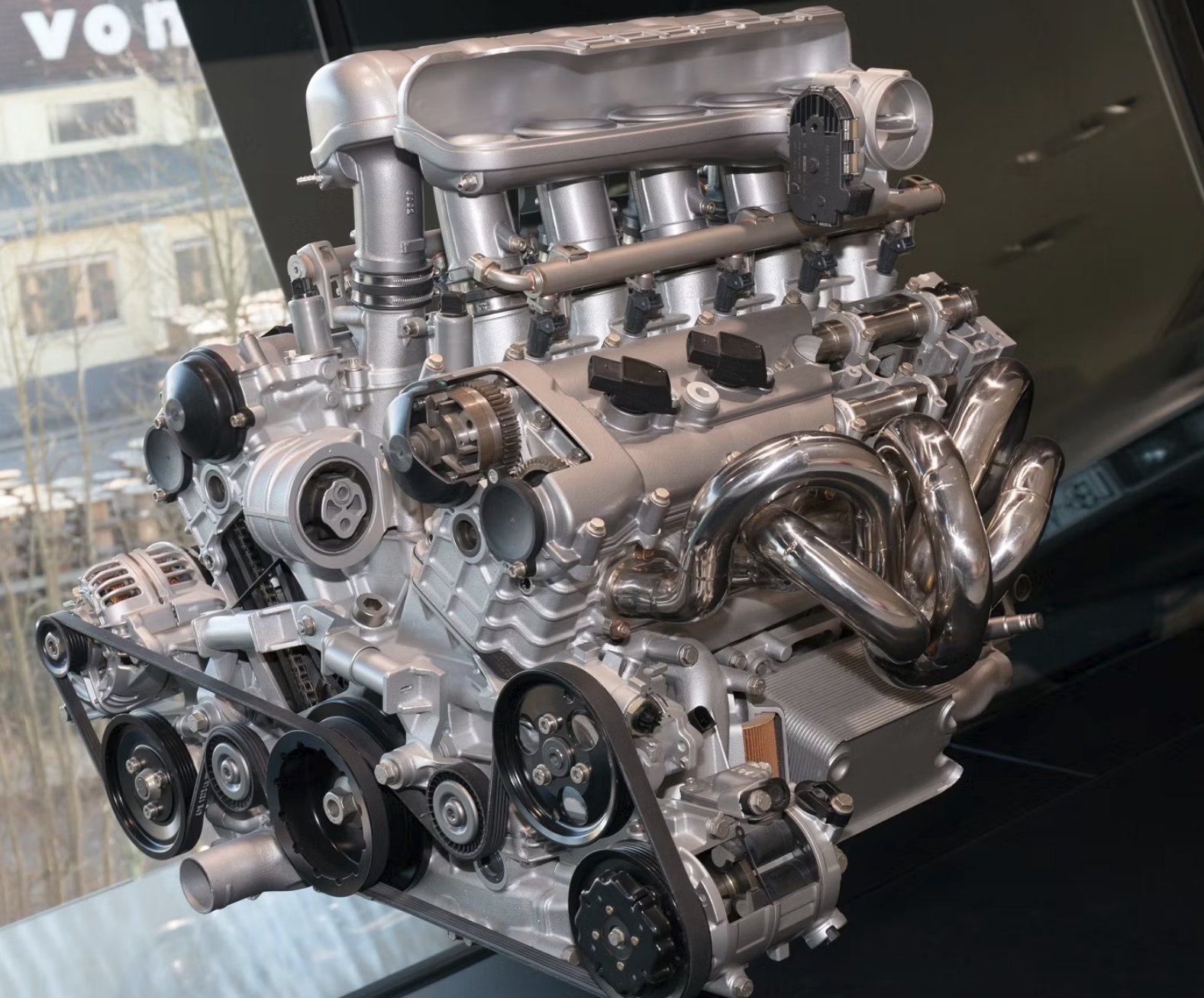

Porsche M80.01

A very close second in Tier 1 but still way above the rest is the Porsche M80.01 68-degree V10. Originally intended for racing, the M80.01 found its home in the Carrera GT supercar, which many value a lot more than the LFA.

Interestingly, this Porsche V10 uses a unique 68-degree bank angle, probably for packaging reasons for the race cars it was designed for. It is even more over-squared than the 1LR with a larger bore and shorter stroke. It similarly uses titanium conrods and forged pistons; it uses no balance shaft, either.

However, this slightly older design has a heavier rotating assembly and valvetrain and redlines at 8400rpm: still very high, but not record-setting like the 1LR.

Tier 2

Viper V10

Starting with Tier 2, I have Dodge’s Viper V10. This is the V10 engine with the longest production. Through five generations, it powered the Dodge Viper as well as a few odd sports cars and the Dodge Ram SRT-10.

The Viper V10 is based on Chrysler’s LA engine, which was also called the Magnum engine. As such, it has a 90-degree bank angle and is the only OHV engine on this list. However, whereas the LA used cast iron block, the Viper V10 used cast aluminum block to reduce weight so as to suit its intended sports car more appropriately.

This engine simultaneously has the largest displacement of any petrol engine in post-war passenger cars, growing to 8.4L in 2008 for the 4th generation. This is also the time when Chrysler introduced variable valve timing, a first for OHV engines.

The Viper V10 uses a 90-degree bank angle and can be considered a V8+ engine. As such, it has loads of low-end torque but is not rev-happy.

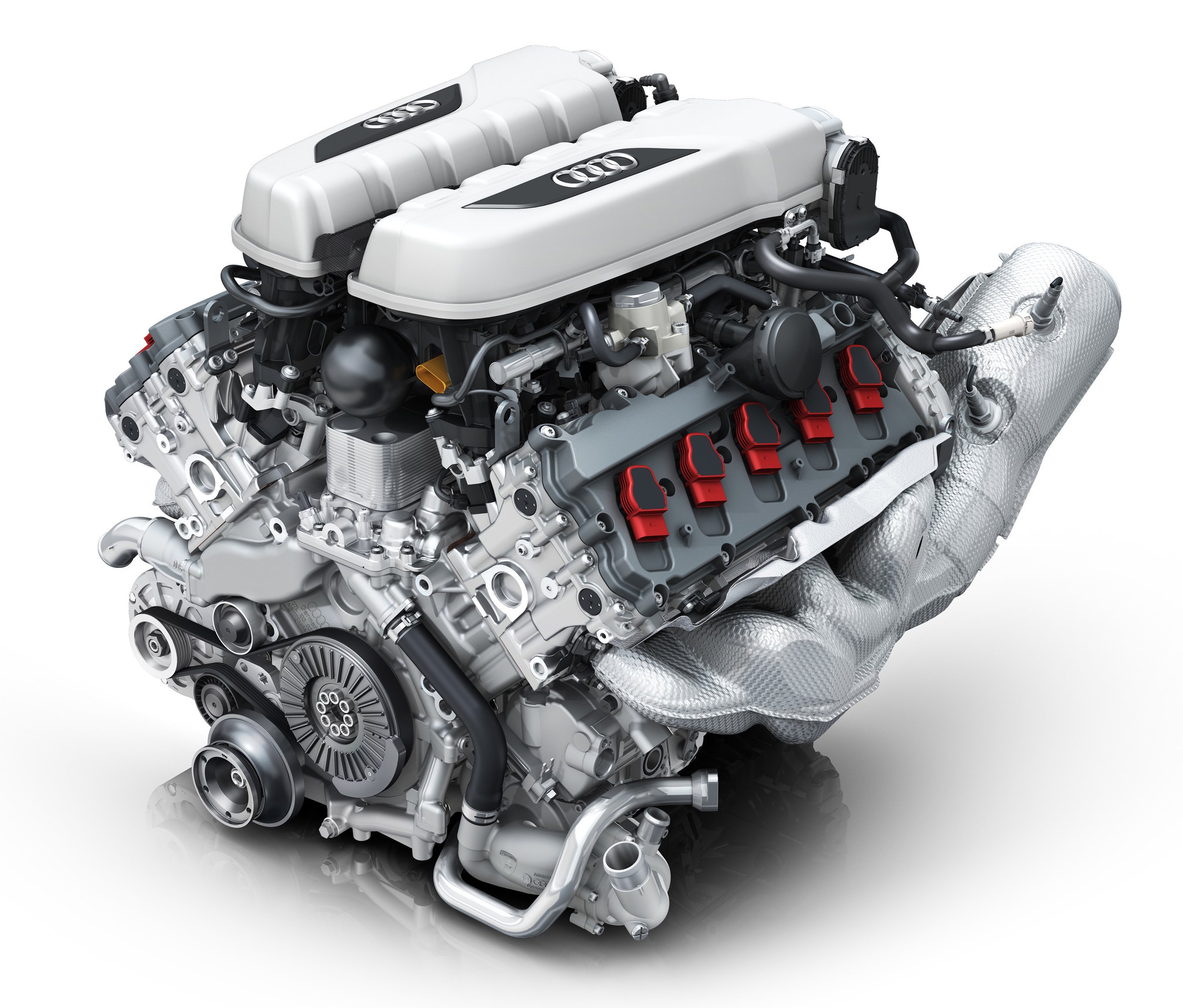

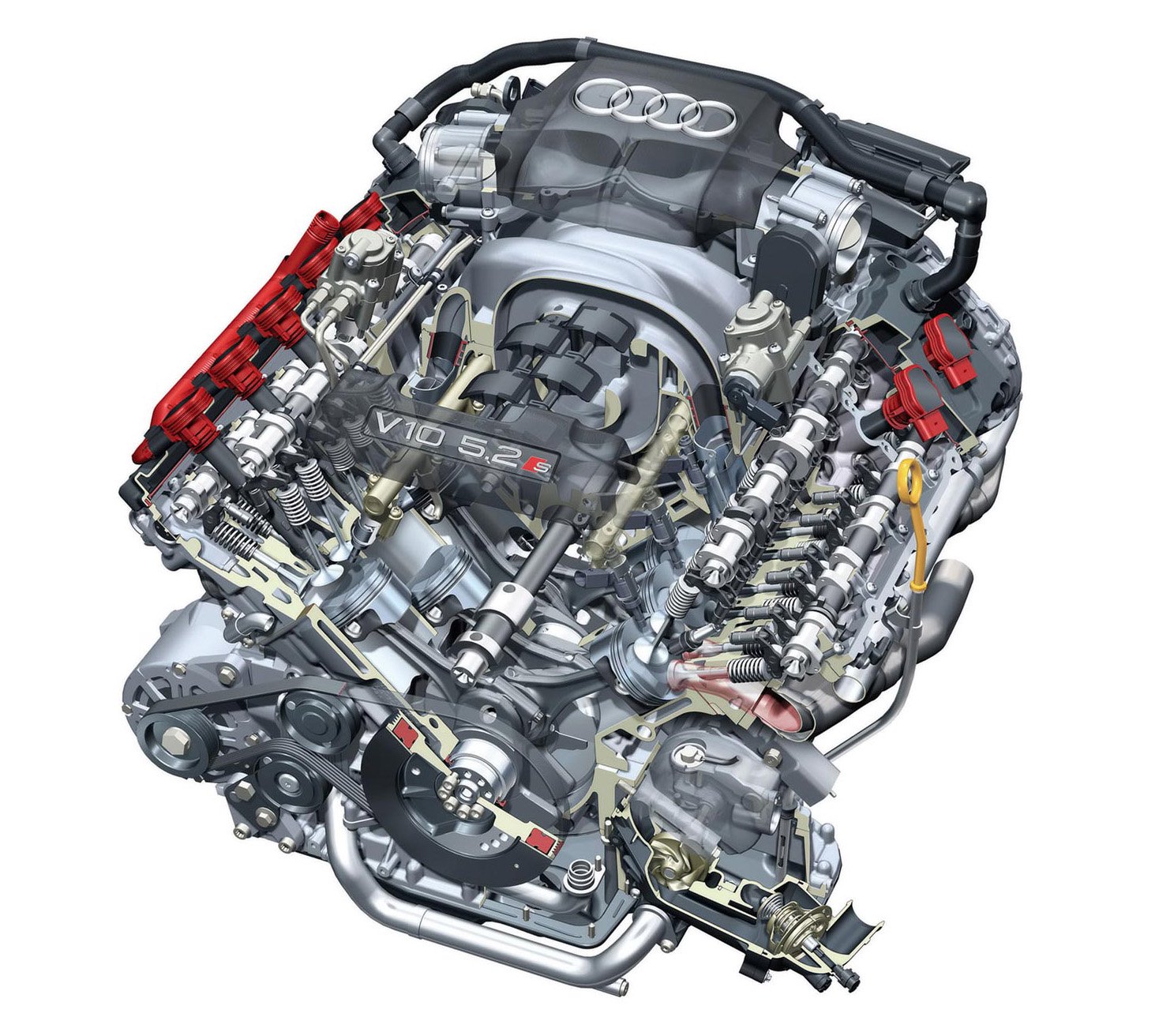

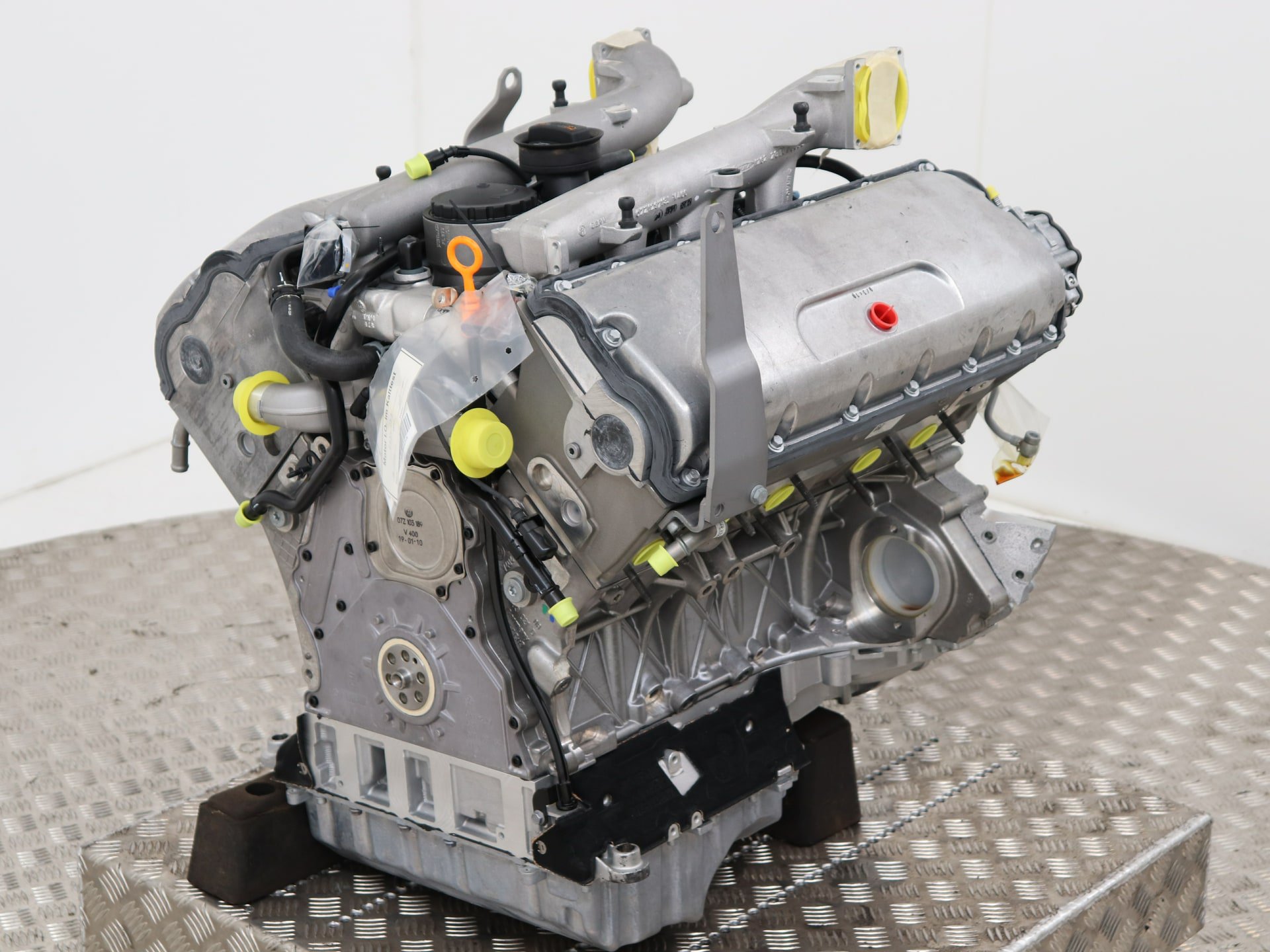

Audi / Lamborghini 5.2 FSI

Second in Tier 2 is Audi’s direct-injected V10 that is a minor evolution of the 5.2 FSI found in Audi’s D3 S8. They shared the same 84.5mm bore and 92.8mm stroke as well as the same 90mm bore spacing. The timing setup is also identical.

However, even though the two engines have the same firing order, the newer one used in Lamborghini and Audi R8 has no split crank journal and is odd firing. It also loses the balance shaft, which results in an engine that revs much more easily. With this setup, the engine is conceptually an inline-5 made up of five 90-degree V-twins.

Naturally, it uses dry sump lubrication with lots of forged internals. It also gained displacement-on-demand during its production run. This is a great sports car engine but falls short of one designed for super cars.

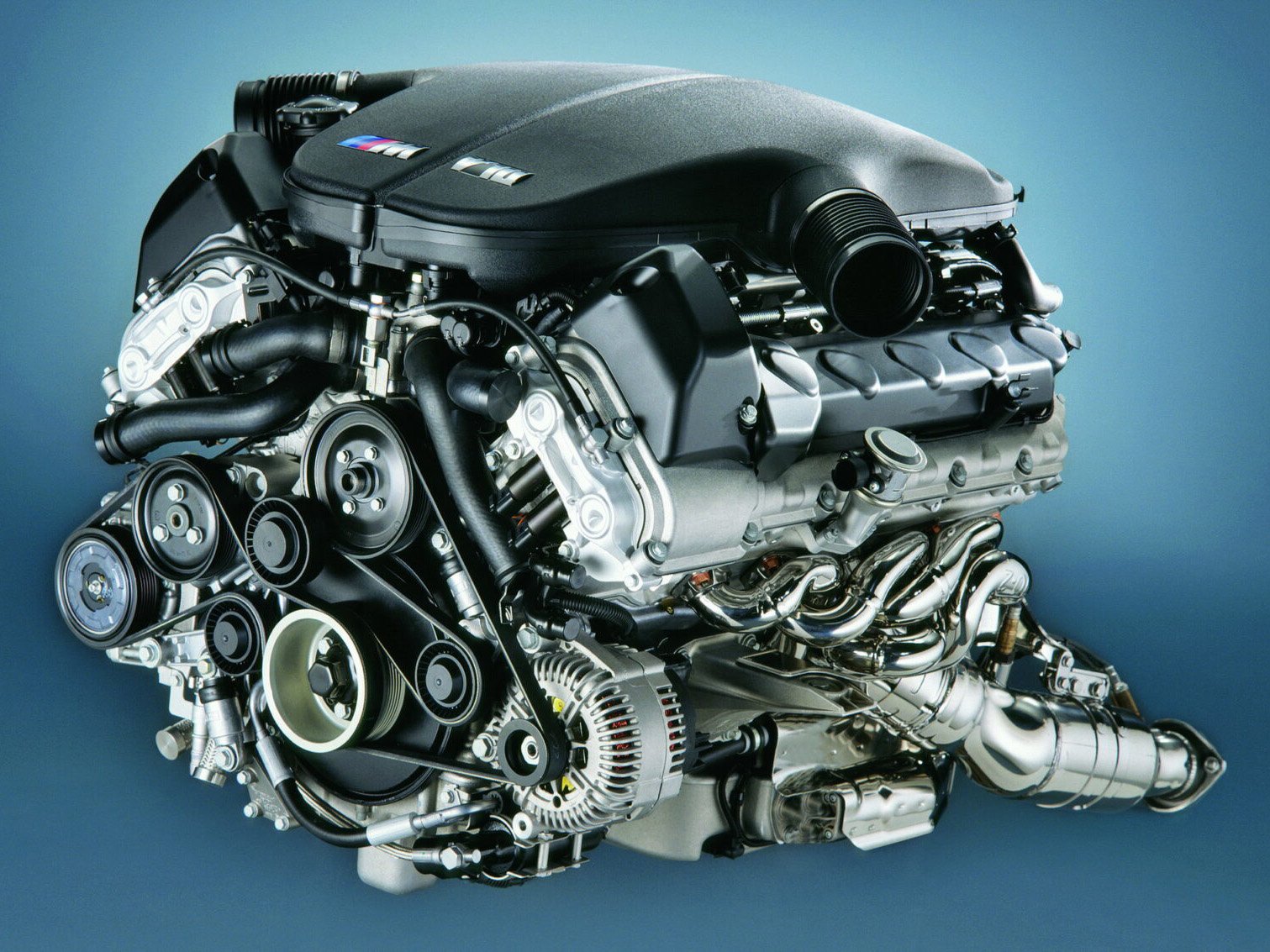

BMW S85

Rounding out Tier 2, I have BMW’s S85. It is similar to the 5.2 FSI mentioned above in that the 90-degree V10 uses the same odd firing order without a balance shaft. However, intended for family cars, the S85 is less high-revving with a lower grade of internal build.

One thing that the S85 has over the 5.2 FSI is the use of individual throttle bodies, which had long been a norm for BMW’s M cars of the past.

One unfortunate point about the S85 is its tendency to throw rod bearings, like many modern BMWs. It is said that this, as well as premature camshaft wear, are caused by bearing clearances that are too tight. Apparently, BMW used bearing clearances that are less than half of the lowest that the bearing manufacturer recommended. Together with long oil change intervals, this caused most of the issues. The remedy supposedly calls for pre-emptive bearing replacement and frequent oil changes.

Another issue with the car is the SMG single-clutch automated manual transmission that is bolted onto this engine in most parts of the world. However, it is possible to swap that part out for a manual transmission as found in US-spec M5 and M6 vehicles.

Tier 3

Audi 5.2 FSI / 5.0 TFSI

Starting with Tier 3, the original 5.2 FSI was what the later sports car engine based on. It had the same block that shared designs with Audi’s 3.2L V6 and 4.2L V10. As such, it had a balance shaft in the same spot as the V6. It revs much lower and uses weaker internals.

This engine was found famously in the D3 Audi S8 and C6 S6 in naturally-aspirated form and in the C6 RS6 in twin-turbocharged form. The slightly de-stroked 5.0 TFSI produced supercar-like power in an unassuming family car and was a high point for Audi. Unfortunately, packed inside such a chassis means that servicing costs are astronomical and parts support is poor.

The D3 S8 still makes for an interesting buy on the used market, while the C6 S6 and RS6 have become rare.

Lamborghini 5.0 SFI

Then, we have the original, port-injected Lamborghini V10 that displaced 5.0L. While this is a different block than the 5.2L FSI unit with a smaller, 88mm bore spacing, there are many similarities, including the timing setup. I would say that this and the two 5.2 FSIs I mentioned above are the three evolutionary stages of the same engine. I mention them separately because there have been lots of confusions about which aspects of the designed are shared.

Interestingly, like the 5.2 FSI in Audi’s family cars, this engine used and 18-degree split crank with even firing order. One aspect that I have not been able to find out is if this engine used a balance shaft.

Volkswagen V10 TDI

Last but certainly not least is Volkswagen’s unicorn V10 TDI. It is essentially two of VW’s 2.5L inline-5 turbodiesels of the era joined at the crank. As such, it also uses an unconventional gear-driven SOHC valvetrain with two valves per cylinder. This is truly unusual, because V10 diesels with two valves per cylinder are common in trucks but all use pushrods. The SOHC design does not change the engine’s sub-4k redline. It is unfortunate that the central timing gear can also crack.

At the same time, this engine is similar to the 5.2 FSI in its use of 90-degree crank with 18-degree split journals and balance shaft for an even firing order.

The engine is fascinating to many diesel-lovers, but it is not a great unit either in performance or in reliability. In fact, Volkswagen’s own V8 diesels of the same period and later exceed it in all regards but rarity. The V10 TDI is therefore destined to be a novelty with a small fanbase. I think it is the only V10 that compares unfavorably to V8s.